Radioactive Sparrow – Dyer: There’s No Escape (1989)

The summer of 1989 was a proper one. In recent years, Britain has grown accustomed to summer months sullied by relentless rainings and gusty scathe. But the summer of ’89 smoldered meanly from moon to moon, broodingly frottaging the mythological instincts of artists whose mission was to inscribe history with a blunted edge.

The Portoman Era stretches out at this stage, Gage and Bargefoot establishing a new mode of operation that would involve driving from Cardiff to Bridgend for afternoon/evening sessions after work during which an EP’s worth would be recorded, or some tracks completed bar the vocals for Heaving Stews to overdub. That was sort of the basic pattern, but it’s more complicated than that: sessions would fold over into each other – when Stews came to record his parts for this album, Kate Talyor and Bargefoot’s brother Niklus (making his final appearance) also trundled into the Shed and new tracks were laid down which Gage and Bargefoot later added to. All of which began the accumulation of yet more surplus material, most of which finally gets forced into commodity through the release of the 52nd album, I’ll Never Fall In Love Again, which finally put the Portoman Era to rest.

That album thus features the remaining tracks from the session that produced ‘Finger,’ featured here, which epitomizes that spirit of making art between sapping shifts – Gage was then working for Cardiff Theatrical Services (CTS) who were the Welsh National Opera’s stage set people, although they also outsourced, of course; in the run-up to Glyndebourne, Gage had been made to work a 36-hour, non-stop shift, mostly painting scenery… The way he felt afterwards, having yet not slept at all, is expressly described in ‘Finger,’ simply because his head had nowhere left to look, captive to hallucinations and attacks of paranoia brought by exhaustion.

By and large, Dyer… is one of those albums that litter the rock scene, featuring two or three timeless classics in amongst a selection that feels like clock-punching filler. ‘In Pursuit Of Pain’ and ‘Season To Be Sad’ have since featured on most Radioactive Sparrow Best Ofs, the former being on of those songs the band felt comfortable playing again towards the end of gigs, no rehearsal needed, and usually well received by audiences, partly because of how it’s played. As a one-off, Bargefoot invented a whole new drumming technique for ‘In Pursuit Of Pain’ which involved allowing the bounciness of drum skins to dictate the actual rhythmic interplay between hands and timbres; it was piss easy to reproduce in concert, if required.

Unlike Bargefoot and Stews, whose waywardness and musical incompetence has long flavoured Sparrow with that crucial Kak-U-Phonic tinge, Tony Gage and Richard Bowers are genuinely talented and naturally competent instrumentalists. Much will be made in posts to come of how Bowers sees the beat like Borg saw the ball, but consider here, on ‘Chat-Up Line,’ Gage’s ability to rigidly maintain a ¾ beat that he has only been played once from the Casiotone keyboard, faultlessly retaining the tempo in order to play along with the original without being able to hear it. Stews’s ‘Chat-Up Line,’ the other stand-out track, was inspired by one of the hundreds of straight-to-VHS USA cheapo horror videos the band were watching week-in, week-out during this period. This particular movie, the title long since forgotten, was about a guy who liked to set his girlfriends on fire… Part of an immense world of films whose legacy remains uncharted because no one has really taken on the critical task of revisiting them in detail. Will this ever happen? It would have to be a Sparrow fan, no question.

Tracklisting:

- Take A Scythe

- In Pursuit Of Pain

- Season To Be Sad

- Lemonade

- Kak Widow

- Bombs Not Jobs

- Finger

- Scoot

- Chat-Up Line

- No Excape

Personnel:

Tony Gage

Bill Bargefoot

Heaving Stews

with

Kate Taylor – vocals on 1, 4 & 10

Niklus – guitar on 1 & 10

Recorded on late May & early June 1989 in the Hut, Ewenny.

Radioactive Sparrow – Old Fruit (1989)

The portoman era coincided with Radioactive Sparrow’s busiest ever year for gigs, playing about twenty shows throughout the year (recordings of most of them survive), which for a band like this was like a world tour. They were therefore more in touch with their craft than at any other time in their history, and it really shows on this album. Following the excitement (and record sales) of Rockin’ On The Portoman, the trio went back into the Hut the following month, and at some stage clearly made a decision to pare materials down to a straight-ahead, unfussy guitar-bass-drums combo, the fabled ‘power trio’ of yore. Made in one day but with plenty of breaks, Old Fruit has a sharp immediacy that bristles with energy and workmanlike efficiency. This was partly due to the technology. The old Tascam 244 that had been used for the previous outing was out of action due to the control buttons having been pressed too hard by over-zealous fingers (Tony Gage has a reputation in this); the machine had to be sent to Swindon for a job turn-around of some 3 months, so a new, cheaper Porta01 was bought. The Porta01 was a much simpler machine and so ambition was scaled down accordingly.

Because of the sensation that the previous album had, on a miniature scale of course, caused, Old Fruit always felt like an afterthought, a bit like one of those contractual-obligation affairs where the band’s full attention isn’t engaged. With time though, it comes over now as possibly the better of the first two portoman albums – the pared down instrumentation and clinical execution making for a much less contrived endeavour. The straight ahead riffing of the opener, ‘The Shops,’ gives the impression that the band are seeking to deliver another Portoman, not least given Gage’s revival of the Cliff Williams single-note bass line from that album’s ‘Sarah Jane Takes The Reigns.’ But ‘Pisces’ seizes the initiative and bombs off in an utterly new direction, Gage’s frantic vocal screaming out the tabloid horoscopes over absurdly forthright drumming from Bargefoot, and Stews’s garment-caught-on-hook guitar.

‘Fierce Desyer,’ played here for the first time, was to become one of a handful of songs that the band would regularly drop into otherwise completely new material on stage, a custom whose logic wasn’t as obvious as deploying a safety mechanism; rather it revealed a natural extension to their total-improv ethos, which has no scruples about wanton self-contradiction. The band were also revisiting the Birthday Party oeuvre on van rides to shows around this time, something that is evident in the tendency to use the multi-tracking opportunity to do a second, distinct vocal take, usually without monitoring the first, along with pursuing subtly monster reverbs, mic’ing the drums by taping a Shure Unidyne-B to the body of an upright piano with the front panelling torn off.

Old Fruit is terse and to the point. Within the overall Sparrow narrative, especially in the context of the Portoman era, it remains as a moment of relative clarity in an otherwise tangled succession.

Tracklisting:

- The Shops

- Pisces

- Firece Desyer

- Catholic Guilt

- Post Mortem

- Big Part

- Bloke I Know

- Slips

- Cindy

- Aga Deer

- World & His Wife

Personnel:

Tony Gage

Bill Bargefoot

Heaving Stews

Recorded April 1989 at the Hut, Ewenny, South Wales

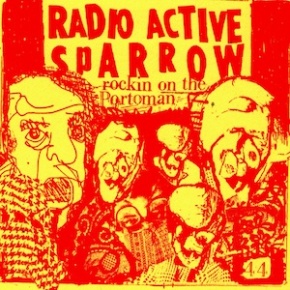

Radioactive Sparrow – Rockin’ On The Portoman (1989)

Rockin On The Portoman marks the onset of the portomam era, a period in which Radioactive Sparrow blew their game wide open, disavowing all the tenets they’d seemed to have observed about one-take, uncomposed pop made up in the very moment of historic inscription. Albums 44-49 constitute an extended requiem for the 1980s, a ghost-written suicide note for the greatest and most complicated decade in recorded popular music. Between the dawn of the 80s and its dismantling in tandem with the demise of Soviet state capitalism, Radioactive Sparrow had accounted for the awakening of adolescent sensibility to the torrid piss of Hades as hegemon while unilaterally resisting the tendency to relinquish unbridled play. Over the course of the next six albums, they dismembered pop music and crafted a vivid botch of its entrails that culminates in the sarcastic adieu of Spume‘s ‘Pube.’ Like the 15-a-week low-budget horror vids they were renting during this period, the music is gratuitously stank, revelled in cheaply close-up, neurotic detail.

The title (and era-demarcation it posed) denotes the group’s sudden and unexpected decision to start recording on a multitracker, namely the Tascam 244 cassette portastudio that Bargefoot had acquired in 1984 and which had been previously used to make demos with his rehearsing outfits (The Sculpture Drinks, Economy Of Islands) and solo experimental stuff (such as 1987’s Song Birds and 1988’s Nonchalance In Vain). The term ‘portoman’ came from Jason Davies relaying news from having bumped into Tony Gage in town some time late the previous year when the latter had borrowed said 244 to record some solo material (1988’s 4-Track Recordings); the way Davies reported it was by casually paraphrasing Gage saying ‘me and Rich[ard Bowers] have been rockin’ on the portoman…’

The reason for the leap into slightly more professional tech was due to the apparent deterioration (see the Angwitch triptych with its various channel cuts and buzzes) of the 1970s National Panasonic radio-cassette (from ca. 1975) whose stereo condenser mics had captured just about everything the band had ever done, using it like a camera, positioning sound sources in relation to the tape machine and performing to it. Over the years, the band developed an advance capacity for production that sidestepped the conventions of the established recording industry. Now, suddenly, they seized the new possibilities wildly and with one hand, the other remaining firmly gripped by the overriding anti-professionalist principles that had long defined their nous.

Throughout the portoman era, which was just over a year long (February 1989 to April 1990) the one principle that hey remained faithful to was the resistance to composing, rehearsing or re-recording music, true to one-shot capture, only now superimposed – not out of any high-minded reverence for some artistic principle but because getting bogged down by any hint of professionalism or industrial orthodoxy strained the joy out of the process. Everything you hear on these albums was made as quickly as it took to play each song twice – the group would improvise the first two tracks, then overdub tracks 3 and 4 at the same time, again without preparation or discussion except to decide who would play what. This went for all the albums made on the multitracker with the one exception of Spume which they spent about six weeks making, dropping in every few days to add a track here and there, even writing lyrics for some vocal parts.

Radioactive Sparrow is a mythology which, through the efforts of a handful of artists, has secretly inscribed itself into real history over the course of the last 32 years. As such, its history has been drastically scaled down from the usual chronology of traditional rock bands. While it is, ultimately, just a story, the fact that it really happened unbeknown to most people has created a situation for its members whereby the imagined and the understood are continually in a state of mutual flux. When Bill Bargefoot was around 6 or 7 years old, he discharged his four Action Man figurines from the anarchically internationalist army which had seen regular frontline service on the walls and in the flower beds of his garden, and had them form a band called Zunk. He got his sister to make them new clothes out of denim and paisley, and his Dad to hastily carve little wooden Strats – the fact that they were still in their army boots even had the advantage of being fashionably ahead of the game, this being the early 70s. Getting a bit carried away with the makeover, he tried shaving one of two bearded figures he possessed – using an unhoused razor blade he inadvertently gouged huge chunks out of the dude’s face, something he then tried to atone for by holding the flame of a match to the surface, which merely made the plastic melt and start bubbling, marking the tiny rocker with post-adolescent pocking. For the next couple of years, until ornithology took over, he would mock up little stage sets for Zunk to do special live appearances in. Tragically his folks were pathological anti-hoarders, and at some stage in the early 90s it seems Bargefoot’s mum sent the old WW2 ammo box in which Zunk was stored to the municipal dump at Stormy Down.

All of which serves to illustrate how, once Sparrow was up and ruining, all its developmental twists and turns similarly unfolded on the miniature scale of a young boy’s imaginative play. This went for both peaks and troughs. On a miniature scale, then, Rockin On The Portoman was an immensely important moment for the band – on the one hand it was their most successful and popular release to date, selling nearly 40 copies (!), while the impact of this sudden ‘success’ on Bargefoot’s life, in particular, was miniaturely momentous. …In October 1988, Bargefoot had registered for the Bachelor of Music degree at Goldsmiths College, London. Goldsmiths had this brilliant little media centre which was equipped with high-speed multiple cassette duplicators (that could run off four D46 copies in 3 minutes flat). In March of 1989, he brought back from a visit to Wales the master mix of the latest Sparrow album (… Portoman) and set about making 40 copies with covers tastefully done in red on yellow card. Having completed the process, he went to his composition class for which he didn’t know (probably because he’d been in Wales, recording) students had been asked to bring a recording of something they’d made or something that was a particularly big influence on them. How fortuitous, then, that Bargefoot happened to have 40 copies of his band’s new album on him! When it was his turn, the played the class ‘Harrat’n Hutt’n’ and ‘The Cattle Bridge.’ The reception among his fellow students was one of hilarity and rapturous approval, and some 10 copies were snapped up at 2 quid a go right there and then. The response from the class tutor, however, was to sourly ask the rhetorical question, ‘Didn’t we get over all that in the 60s?’ Bargefoot was deeply shocked by the level of cynicism on the part of the lecturer, Tim Ewers, along with its obvious disinclination to any sort of encouragement. At aged nearly 23, he wasn’t troubled so much on a personal level, but the fact that Ewers was inclined to display such an attitude to 18-19 year-old hopefuls was very depressing. It triggered the beginning of the end for Bargefoot at Goldsmiths, intent thereafter to openly goad not only Ewers but several other staff who peddled dishonest and irrelevant orthodoxy pap to their first years. Rather than anyone seeking to meet the challenge he posed, he was duly shown the door come June, something for which his piano tutor, John Tilbury, actually congratulated him – Tilbury, who, it seems, always had an uncomfortable relationship with his employers (they certainly undervalued him), had by then become a Sparrow fan and had passed several albums on to the legendary composer John White who himself became a long-term champion of the group (of which more in later episodes) and started playing them in his lectures at the London College of Music. This is what I’m talking about with Sparrow being a rock & roll history in miniature: for the likes of Peter Green and Syd Barrett, suddenly selling loads of records, becoming rich and famous, being misunderstood and getting undone by LSD, resulted in a career-wrecking crash; Radioactive Sparrow hit their big time selling 40 copies and Bargefoot got kicked out of college…

The music on this album tries to go everywhere. ‘Harrat’n Hutt’n’ bursts into life as the album’s opener, almost a manifesto in the extremes of what was suddenly available to the Kak imagination now that overdubbing was legitimised – it’s a wild celebration of ludic exaggeration set to a backdrop of incompetent free jazz. The lead vocal (and its lyrics, as such, though they’re hard to decipher) is based on a tape of Scottish traditional piping by William McLean, something that had come into Bargefoot’s possession utterly by accident. A week or so before the recording, Gabriel ‘Gabelli’ Sobin had stayed with Bargefoot at his halls of residence in Camberwell (the legendary Dover House on Cormont Road, hardly halls, really). They had indulged in a four-day extended derive, effectively, walking aimlessly around London, avoiding returning to the room they were staying in until 3 or 4 in the morning. As if to ceremoniously acknowledge the feat of their exhausting mileage they would sit on returning for 30 minutes or so listening to these bagpipes in quiet contemplation. The album unfolds from here through a broad range of styles and methods, the trio greedily raiding the pantry of ideas previously remote to their resolutely spartan phonography. ‘Sarah Jane Takes The Reigns,’ sung by Stews reading from page 3 of the Sun supplementing their topless babe with gratuitous punning themed for the Seoul Olympics (it was an old copy dredged up from God knows where), sets out to sound swankishly slick before capsizing the decorum of cool for its chaotic chorus slide riffs. What used to be side one closes with a composed (though unrehearsed) song about what was then a new news phenomenon, global warming – the crowning moment of ‘No More Winters’ is Gage’s echoing ‘the ozone layer’ in a booming Gloucester accent.

Even though Emma 100-Fingers was absent from the music, she provided the album with its superb cover art.

Tracklisting:

- Harrat’n Hutt’n

- Sarah Jane Takes The Reigns

- Music For Baby

- Empty Pockets

- No More Winters

- The Cattle Bridge

- Pond

- Bess Fren’s Girlfren

- Kim

- Please Tell Lisa

Personnel:

Tony Gage

Bill Bargefoot

Heaving Stews

Recorded in the Hut, early March 1989

Radioactive Sparrow – Burst! (The Hidden Real Truth Behind Angwitch’s Secrets) (1989)

Regular visitors to the online Kak circus will be familiar now with Sparrow’s rule of exceptions whereby the material initially considered the least worthwhile when putting an album together turns out to be stronger and more interesting than what’s originally favoured. In the case of Burst! we’re now two layers deep, a whole album of rejects already having been mounted and framed as Blood, Piss & Burps, whose content was deemed album-worthy soon enough to give it a series number (43), but by the time the forgotten material here was rediscovered, some 6 months later, the band had already moved on past album 47, and were deep into the portoman era. Rather than making it an album b-side (which wasn’t so practical with hour-long helpings, since C120s are notoriously chewsome and snap-happy) Burst! has always been considered an alternative album 43, even though, out of the three albums they ground out at the Angwitch session in January, this turns out to be at least the other two’s equal.

The first three songs clear up the last of the fucked-tape, flat-battery session (which provided no numbers at all for Blood, Piss & Burps), probably the strongest tracks from that sitting. ‘During War Time’ is so wonky that, even while it makes a great track now, it’s really hard to tell what it would have really sounded like – certainly it seems to be an exceptionally inventive performance which the trio were very eager to listen back to, so consequently this would have exacerbated their dismay at its bent capture, a moment of poetic greatness lost to the indifferent motor of their beloved Panasonic. Then we get three unfinished, aborted attempts from the main day-time Hut session, followed by three complete songs from same. The second of these, ‘A Big Lorry Full Of Sand & Gravel’ is an early Gage stunner, shaped by his classic sardonic take on the ordinary. The album closes out with two final pieces from the small hours, Stews’s percussion on ‘Oh Darlin” way ahead of its contemporary attitudinal post. Rendingly, this is Emma 100-Fingers last appearance until the band’s 80th offering, Brownstar, the following century.

Tracklisting:

- Elast

- Undies Per Chance

- During War Time

- Ethyl

- Ladies Charm

- Rocking For Your Mother-In-Law

- My Best Friend’s Girlfriend Reads Minds

- A Big Lorry With A Delivery Of Sand & Gravel

- Customer & Long

- Oh Darlin’

- Dockland Fantastic

Personnel:

Emma 100-Fingers

Heaving Stews

Tony Gage

Bill Bargefoot

Recorded in the Hut 8 January 1989

Radioactive Sparrow – Blood, Piss & Burps: The Truth About Angwitch (1989)

Since very early on a favourite routine for Radioactive Sparrow has been the improvised choir, every member of the group contributing. ‘Rikety,’ which gets Blood, Piss & Burps moving, is a particularly fine example. During the academic year 1988-89, Bargefoot was in the first year of a music degree at Goldsmiths. He was never to make it to the second year, of which more later on. One of the things he hated most was membership of the university choir which was compulsory for anyone who didn’t play in the orchestra, consigning students to weekly 2½ hour rehearsals led by Roger Wibberlely whose schoolmasterly manner was excruciating in its patronizingly lumpen don’t-be-a-spoil-sport cajoling. Bargefoot would sit in the basses, at the back, next to Bruco Lava (future Sparrow member who also got kicked out of Goldsmiths), and to relieve the suffering would frequently improvise incongruous counterparts to what was being yawningly wailed around them by Good Honest Men. The glossolalic theme and its sustained note auto-response that Bargefoot introduces at 3’25” is derived exactly from such instances of self-saving subversiveness.

Blood, Piss & Burps was compiled a few weeks after Angwitch was packaged up, after it became clear to the group on revisiting the tapes that they had initially underestimated most of the stuff they’d felt on the day didn’t come up to scratch. The songs selected for this, the second pressing of the fruit bagged in January, were pretty much self-selecting in so far as the album’s continuity and narrative seemed to effortlessly fall into place. The are moments of unusually open song-ness (‘Northlands,’ ‘Sun Woman Body Line,’ and ‘Eggly & Hamly’) alongside tousled cribbings of avant-partyism (‘Views Of Spain’ and ‘3 O Clock On Xmas Day’).

This album features an unusually high level of lyrical content appropriated from the diverse texts left to soak up the beer, sweat and fag ash on the Hut floor, mostly old letters and sodden rags of News of the World colour supplements. Perhaps one of the stand-out tracks, ‘Hey, Boy, What’s Your Problem (With Knowledge)?’ has Stews tripping up the logic of epistemology, aiming his invective at A.J. Ayer, while rapping out passages from his The Problem With Knowledge.

The gruelling 16-hour session that produced most the material for the three Angwitch tapes came to an end with ‘My Head Is Empty.’ It’s nearly 5 in the morning and Bargefoot dredges up one last riff nuanced with a fading optimism; Gage is given the microphone and invited to sing, but when he tries, he discovers the cupboard is bare, there are no more berries left to squeeze juice from. Some years later, of course, they would come to recognize such situations as indispensible in pursuit of the Kak dream, having ‘no ideas’ and just as scant ambition being prime directives.

Tracklisting:

- Rikity

- Northlands

- Views Of Spain

- I’ll Never Forget You

- Sun Woman Body Line

- Owen, Watch Where You’re Goin’

- Hey, Boy, What’s Your Problem (With Knowledge)?

- Eggly & Hamly

- In The Hay

- Baby In The Bucket

- 3 o’ Clock On Xmas Day

- Burper & Farter

- My Head Is Empty

Personnel:

Tony Gage

Bill Bargefoot

Emma 100-Fingers

Heaving Stews

Recorded in the Hut during the first week of January 1989

Radioactive Sparrow – Angwitch (1989)

Angwitch is, effectively, a trilogy (bunched in with album 43, which is a double, all three recorded on the same date), agonisingly the only albums to feature what must be considered Radioactive Sparrow’s ideal line-up. It’s not for nothing that the only Radioactive Sparrow t-shirts printed to date featured the quartet that appears here, a design by Gage that groups together the four faces each wearing the same pair of cheapo kids sunglasses. You really get a sense of how much bigger than average Bargefoot’s head is when you see how much smaller the shades are on him than the other three.

The recording of Angwitch was a gruelling business, the main session lasting 16 hours, starting in the Hut at 11am and finishing 5 o’ clock the following morning, all because they kept thinking they hadn’t recorded enough decent material to make up an album’s worth. One of the great beauties of producing work in this way (aimlessly recording limitless amounts of songs made up on the spot) is that what seems like rubbish at first so often turns out to be unexpected genius after a few weeks, months, even years cooling off – the ever-reinvented contexts of time’s eternal relay redefining the character of captured actions. Consequently, the next album, Blood Piss & Burps: The Truth About Angwitch and its flip-ternative Burst! are probably even better than what was originally selected. This exhaustive wringing out was supplemented by a living-room session without Gage the night before, during which the tape inexplicably went bananas in the machine (probably due to low batteries) resulting in wonky, sped-up songs to the group’s initial dismay. The two sides of the original C60 opened with tracks from the first Meltdown of the year for which the band wore floppy-flappy woollen hats that wobbled to the lilts, which got easy laughs.

It’s easy to see why they’d have been so restless with what they were producing. By this stage in their development the intensity of content was increasing, the hunt for lyrical nuance and convincing riffs was at risk of becoming a tad urgent – they hadn’t yet learned to fully believe in the mantra ‘the worse the better.’ Not that they were anxious about any of it, mind: the persistent single-mindedness of Stews’s ‘Doodlin” is testament to their customary arrogance remaining immune to the threat of professionalist imperatives.

Angwitch is about gaps and holes, failures to make clean connections and direct contacts. On ‘Ripper’ Stews sets about trying to improvise lyrics around threats of physical violence that rhyme with the name of its imagined victim, but superbly he never quite manages to make this work: ‘Hit you into the chest, Lest/Hit you into the groin, John… Kick you into the knee, Charles/Wanna glass in your face, Chase?’ Similarly, ‘Crush Marbles’ sees Bargefoot try and relate a story based on Hauptmann’s Bahnwärter Thiel, which never quite manages to make any sense, while on ‘Fly In My Eye’ his utter ineptitude at singing and playing the bass at the same time makes for an excessively disjointed lopsiding that virtually renders the effort devoid of any musical logic. ‘Doodlin,” on the other hand, is an impish enactment of the stuck record, resolutely refusing to expand on an idea.

The word ‘angwitch’ came from ‘Drain Dreams’ on the previous album, Jupiter, in which Gage constantly fails to enunciate most of his lyrics properly.

Tracklisting:

- Why Oh Why

- (Please) Don’t Break My Heart

- Fly In My Eye

- Ripper

- Doodlin’

- Je Ne Sais Quoi

- High Condriact

- O Mummy Am I Monday

- Crush Marbles

- Chocolate Drop

- Cos She Was Bored

- Fish Pancake

Personnel:

Emma 100-Fingers

Tony Gage

Heaving Stews

Bill Bargefoot

Recorded in the Hut, January, and at Chapter January

Radioactive Sparrow – Jupiter (& Sheba) (1988)

Until the onset of the portoman era (albums 44 through 52), Radioactive Sparrow were in a period of transition during which the genius that is Tony Gage became acclimatised. His impact, though, was pretty much immediate and it’s with this album that the group really shifts up a gear. The sharpness and invention on Jupiter are already several degrees higher than Double-Top, especially once ‘Severed Head’ kicks in, Gage’s live drumming on the Synsonics more energised and committed than anything on previous outings. In fact, this level of energy and commitment is more subtly evident on the previous track, ‘I Love That,’ in which Gage plays the whammy guitar slightly to the left in the stereo image: look out for his wobbly lead interjections and rock-enthusiasm glissandi.

Jupiter is a classic. The title was randomly plucked from the air in a manner even more casual than the artwork and packaging from this period. The fact that Radioactive Sparrow’s forty-first album was called the same as Mozart’s forty-first symphony was pure coincidence, although it’s hard not to concede that there must’ve been some connection made deep in Bargefoot’s or Miss 100-Fingers’s subconscious (it was one of them that thought of it while putting together the final package in Howard Gardens library where they also printed the covers).

This was Brooce Boyes’s final appearance (apart from a minuscule contribution to 1990’s Bush Of Ages). He was to supposed to have been at the Double-Top: Sheer Talent weekend (which would have seen the convention of the ultimate all-star cast of Bargefoot/Stews/Gage/100-Fingers & Boyes – but this was tragically never to be) – his ancient Ford Capri broke down and he never made it out of Plymouth. The glimpse we get of Brooce in this final frame is of an instrumentalist utterly fluent and assured in the Kak discipline, especially on his fretless bass, often fed through a phaser; as a vocalist, however, he betrays the sensible detachment of one who has succumbed to the adult ordinary, a grown-up patronising a liberal conformism that has left the field of adventurous play, but looks fondly back with ironic detachment on ‘those crazy times… weren’t we mad!’ … As if it’s just another fun pursuit in a world of democratic equivalences, forgetting for good that the historical inscription of cacophonic pop music was, and remains for the band, ‘as serious as your life.’ in his uncharacteristically scant vocal contributions (on both Jupiter and Sheba), he sounds distinctly outside. No one can recall a falling out at this stage, yet clearly there was some antagonism following the sessions because the opening and closing tracks were originally titled ‘BB RIP’ 1 & 2 , which seems a little mean now, so they appear here re-titled after the song’s chorus, ‘Hot Chocolate Jon.’

Most of the album comes from a single Hut session on a December Saturday by the full assembled quartet, with three tracks recorded the night before by Bargefoot and Boyes (plus four more on Sheba). After the distinctly rockist approach of the previous album, Jupiter refreshingly revives the Casiotone MT403 keyboard and Synsonics drum machine rhythm section that had characterised much of the material made in 1987. ‘Nottingham Sunny Day’ is the album’s glorious centrepiece, an 8 1/2 minute song led off by Emma 100-Fingers’ brass-toned parpy trumpet sound, Gage and Boyes on duelling basses and Bargefoot delivering vocals through a phaser. The quartet generates an extraordinarily hypnotic vibe that at times seems to melt and blur into a single multilayered engine, basses resembling swarming bees, ticking industriously away with the Casio’s fantastically austere single-snare preset beat.

Typically, two whole albums’ worth was recorded, and the originally unused material is available here for the first time as the b-side, flip-lementary album, Sheba. Some of its tracks match the edge and intensity of Jupiter, while others were simply left off the main release because they’re either accidentally cut short or they because they prematurely run aground. ‘You Let Me’ features what was probably the last appearance of the Kak guitar, whose 2-inch action and partially dismantled sound-box defined the inimitable sound of the early anthem ‘Long Live The Kak With H2O.’ The cover selected for Sheba is a 1981 110 print that shows the steps in the back garden of Albert Cole, whom ‘Nottingham Sunny Day’ is about, his dog Peppy (who also gets a mention in the song) trotting merrily down them.

Tracklisting for Jupiter:

- Hot Chocolate Jon 1

- I Love That

- Severed Head

- Lemon Chill Fallin’

- Drain Dreams

- Laugh With Me

- Nottingham Sunny Day

- W.N.O.

- Husbandry

- Cook This Tonite

- Under Th’ Mowntinn

- Hot Chocolate Jon 2

Tracklisting for Sheba

- Eradicating Vega

- Chronic Misfire

- You Let Me

- Wish Upon The Moon

- W.N.O. Castrated

- Unejaculate

- I Don’t Wanna Dance

- Side Slip

- Sheba, Sheba, Fat Now

- Hierarchy In The UK

- November Trees (For Yolande)

- Desperate For A Reason

Personnel for both:

Bill Bargefoot

Heaving Stews

Tony Gage

Emma 100-Fingers

Recorded in the Hut, December 1988

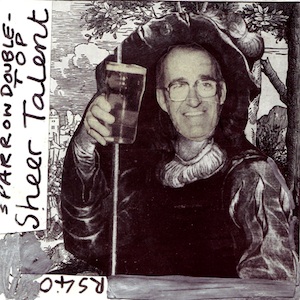

Radioactive Sparrow – Double-Top: Sheer Talent (1988)

Another unique moment in the Radioactive Sparrow story, there was never another occasion quite like the late-November weekend for which the band gathered to make their fortieth album. Sparrow membership has always been a nebulous attribution, but had you pressed the band to proffer a definitive line-up in the autumn of 1988, this quintet here would probably be it, even though Brooce Boyes was supposed to have taken part – at that time he drove a 70s Ford Capri that was more trouble than it was worth, and on this occasion it had failed to start, leaving him stranded in Plymouth. The album was recorded on the Saturday, working till late, then going to Southerndown beach on a moonless, pitch-black night, and walking towards the water’s edge on a very low tide, unable to see a thing, after which they probably made sure they got to the Three Golden Cups for last orders. On the Sunday they wrapped up proceedings by playing a set at Chapter’s Meltdown, a sort of open mic night that always featured a couple of headlining acts from around 10pm, but if you turned up before 7 you could usually get at least a 10-minute slot. This was the first of many occasions when Sparrow would record during the weekend then play a Meltdown set as if delivering a public report straight from the furthest frontiers of Kak, albeit to ignorant, indifferent ears. On this occasion, whoever was asked to look after the tape machine forgot to press record until half way through the last number, a stage conjuring of ‘Bile Vial,’ which they’d recorded the previous day. That 3-minute extract forms the last part of the complete 13- minute track on the album itself, closing out what used to be side one of the cassette. Even the glimpse offered here suggests that it was a amazing show, and the crowd’s wild enthusiasm is followed by the compère’s expressions of disbelief: ‘Radioactive Sparrow, c’mon! Who said we never have anything different? Good God!’ The lucidity, fluidity and sheer energy of the performance provides as good an account as any of the exceptionally sweet spirit of collectivity the group enjoyed at this moment in time. The party atmosphere had infused the whole weekend;afterwards, Emma 100-Fingers said it felt like Christmas. The final track on the album, ‘Back In The Van’ (released for the first time here), was recorded on the drive from Pontcanna to Roath where they ate at a Chinese restaurant after the Chapter gig. It features a lead vocal from Miss 100-Fingers who also contributes increasing amounts of backing vocal as the album progresses – clearly she was overcoming an initial shyness with the voice, and we’re left here with yet another tantalising might-have-been had she continued to play a part in Radioactive Sparrow over the ensuing years.

A lot of Radioactive Sparrow albums are made up of tracks from different sessions and organised into a continuity retrospectively, even though the initial intention has usually been to record the whole thing in one go, in its intended listening sequence – in other words, to the ideal means of production would be to experience the actual album as such while it was being made, not just improvising pieces one at a time then seeing what they had (like, say, Can) – Kak has always been very much about enjoying hearing music you want to hear for the first time while actually making it. In the end, relatively few albums came out like that, but this was one of them (as were soon-to-be-posted Old Fruit and Deathcunt). It should be born in mind, then, that the pacing of the album, its narrative peaks and climaxes, are something the band were conscious of while they were playing. ‘A Hate Of Great Twats,’ an excellent Stews opener, limbers up and scopes out the territory before Bargefoot kicks off ‘Spinning Bowl,’ a song about that old-school cylindrical fair ride which spins at increasingly high speed until they take the floor away so people are left pinned to the fucking wall by its centrifugal force. Bargefoot announces the riff for ‘Spinning Bowl’ before playing it: it had resided in his head since the age of about 7, when he originally made it up, in those days calling it ‘James Bond.’ One of its lasting charms is that it constantly spirals out of control, as if the wild force of the spinning bowl itself has interfered with the band’s earnest endeavours. This is in fact due to Bargefoot’s tendency to screw the meter and fall out of time at certain points due to heightened intensity, something that, along with Stews’s ante-musicality, would come to define Kak’s essence.

The shortcomings of Sparrow’s one-shot Panasonic capture of the full rock line-up in the Hut have already been mentioned (see You Keep A Rockin). The technique they used was to put the vocals through the old Zenta 10 watt amp and place it next to the tape machine if the vocalist wasn’t using the usual method of singing close to the condenser mics themselves. By the third song, however, it seems as though either the amp or the recorder got moved, because from then on the mic’d vocals are too low in the mix. So, just as they’d done for You Keep A Rockin, they got the 4-track out to overdub an additional voice part. Except this time, they sorted it out straight after the main session, with everyone present, so for Gage’s ‘St Patrick’s Caravan’ the whole group were joining in on the choruses like carol singing – on ‘Bike Vial’ this descends into a swirling chaos of vocals and random interjections. ‘Bile Vial’ had initially been made up on the spot during the Sheffield Take Two gig. Its premise – Bargefoot’s mildly tritone-tickling riff supported by Gage’s playfully scalic bass line – was one that was easy to strike up again. Here we get a long rendition in two parts from the Hut, with the exuberant live segment faded in at the end. During the many-gigging 1989, such germs would become a fall-back, the band often finishing up sets with ‘Spinning Bowl,’ ‘Flayed Alive By Lesbians’ and ‘Bile Vial’ as would-be standards, although this would never be planned or discussed, and certainly never rehearsed – it just seemed to feel right at the time to take a step back from what would otherwise usually be a wholly improvised show.

Both halves of the album’s title came from the annual coverage of the darts world championships on TV, a really special 70s/80s phenomenon in the UK when the sport briefly became a universally popular, for-all-the-family, prime-time spectator sport. Its superstars, the likes of Leighton Rees, Jocky Wilson, Eric Bristow and Cliff Lazarenko would be fantastically unfit, draping sizeable beer guts with comfort-fitting nylon short-sleeved shirts, stepping back from the oche to glug from what was an immoderate standing of pints and several ardent puffs on chain-smoked fags. To Radioactive Sparrow, the sport’s utterly anti-athletic ethos was brilliantly cacotopian and seemed to speak directly to their cultural sensibilities. For those who aren’t familiar with the game, ‘double-top’ is double-twenty (i.e. 40), the highest check-out double on the board; ‘sheer talent!’ was a hyperbolic exclamation by the sport’s iconic Geordie commentator Sid Waddell following some admirable feat such as consecutive maximums (one-hundred-and-EIGHTY) or a 161 checkout finishing with… double top; the cover star, raising his pint in a toast to Radioactive Sparrow’s great achievement, is Jim Bowen, a veteran UK stand-up comedian who used to host the sport’s highly popular and fantastically unslick spin-off gameshow, Bullseye, on channel 4.

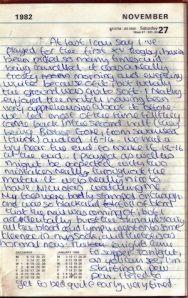

Over the years, there was a tendency to have all kinds of texts lying around the Hut for a vocalist to grab whenever they felt in need of a spur – tabloid press, Reich’s Function Of The Orgasm, old letters, and Bargefoot’s old diaries, the latter frequently proving the most entertaining option. Stews was traditionally the one to select an entry, and this had something to do its their shared past, school rivalries and long-dormant gossips. On this occasion he simply picked the same date, November 29, from 1982, for a tack they’d already recorded for the purpose once they realised they would be needing overdubs anyway. ’27/11/82′ features the whole diary entry [pictured below] read out by each member of the band (except Miss 100-Fingers) in turn, Bargefoot’s voice sped up and Stews’s slowed down.

Ultimately, for all that it’s an uncharacteristically straight ahead set of songs, closer perhaps to what they sounded like in gigs at the time. Certainly there’d be nothing as rocky as this for a good while.

Tracklisting:

1. A Hate Of Great Twats

2. Spinning Bowl

3. Happy Herring

4. St. Patrick’s Caravan

5. Bile Vial

6. Snow

7. 27/11/82

8. Flayed Alive By Lesbians

9. After Flayed

10. Mean Machine

11. Sound Of The Oppressed [previously unreleased]

12. Back In The Van [previously unreleased]

Personnel:

Heaving Stews

Bill Bargefoot

Emma 100-Fingers

Tony Gage

Guy Williams

Recorded at the Hut, November 27 1988 & at Chapter Arts Centre, Cardiff, November 28 1988

Radioactive Sparrow – 39/Trans/Flied Piecatcher (1988)

This is a messy gluing together of various things recorded at Preswylfa, and from two gigs in June and September, between making 1730s (recorded in April) and Double-Top: Sheer Talent (October), a period which saw the beginning of Brooce’s withdrawal. It’s the first album to feature Tony Gage, but it’s not really his first Radioactive Sparrow album, partly because he’s not on all of it and where he is he’s not really him yet, quite. His joining the group came about because Bargefoot had booked the band to play at El Sico’s (later more famously known as TJ’s), Newport, and about two weeks before the show Brooce pulled out because of a dispute partly relating to the band not being paid (Stews was already otherwise engaged, so he couldn’t make it either). Bargefoot, Stews and Miss 100-Fingers looked around for a replacement, giving tapes to potential suitors – Radioactive Sparrow must be one of the few bands in history who needed to audition for potential recruits’ approval rather than the other way around. After a few knock-backs, they dared to ask Gage if might be up for it, though they imagined it was very unlikely. To their thrilled amazement he said yes, whereupon a warm-up session in the Hut was hastily arranged which would introduce him to the basic approach of Kak’s instantaneous song-craft (tracks 2, 3 & 12 on the album came from this session).

To the band’s horror, when they turned up for the gig, they were told by Trilby (Mr. Siccolo’s wife, the ‘TJ’ for whom the venue would later be renamed) that it was ‘Rock Nite’ to which most of Gwent’s biker fraternity generally turned up. In their panic, the band came up with a plan to try and sound as normal and rocky as possible, while urgently summoning Chris Hartford from London to come down and open for them, basically as canon fodder. Both plans were lamentable in their outright cowardice, for which Kakutopia now apologises to the history of human endeavour. It is a testament to Hartford’s sense of history and his commitment to it that, despite the fact that he was in the middle of his finals – and had just come out of one of an exam – he got on the next train, turning up literally just in time to go on. His set is included here, partly to give an indication of how the crowd responded, but also because it’s a vintage document of Ded Pan Chris (as he was known during that period) featuring all his classics like ‘Freaking Out On The Half-Past One Ferry To The Channel Islands’ and ‘Times Are Hard If You’re Just A Torso’ as well as more experimental pieces like ‘Summer ’17.’

Tracks 5, 9 & 13 come from the TJ’s performance. They’re pretty dull, by and large. They opened with ‘Memories Of Roman Times,’ the title track of the very first official, now lost, album, played and sung from memory by Bargefoot, improvising the verse lyrics (the refrain, ‘I tell you you’re a cow, but you won’t be in a couple of weeks in/Memories of Roman Times/Flashing through your brain…’ is preserved from the original). ‘Neighbours In Transit’ is revisited from the recent Skorpion Sundy Rising, while ‘Who Left The Gas On’ was totally improvised, the chorus referring to Emma 100-Fingers’s mondigreen of that year’s continental fave, ‘À Cause Des Garçons.’ The whole experience was terrifying, but the crowd of some 80-plus bikers were apparently in a lenient mood, preferring to heckle rather than throttle, their light touch more than likely suggesting that they thought the band really was just hopelessly shit in a pathetically tragic, but unthreatening way. The worst the band got was stuff like ‘that’s enough, now fuck off!’ and ‘they need a new guitarist.’ Although, bizarrely, Miss 100-Fingers did suffer heroically. She was playing keyboards at the side of the stage, where a group of biker chicks kept whacking her on the shoulders with their handbags, and that did leave several bruises. For which, eternal respect.

The remaining live cuts (6 & 10) come from a gig at Sheffield’s Take Two, some three months later, Heaving Stews restored to the front of the show, and introducing Guy Williams as Ceri Davies’s drumming replacement until Richard Bowers joined the band in the latter part of 1989, which represents the real beginning of Tony Gage in Radioactive Sparrow, in that it was a proper Sparrow gig, no messing. ‘Telephant’ revisits the acerbically confrontational one-note stamp of April’s Clwb Ifor Bach performance (see 1730s, album 38), Stews this time aiming his invective at the recent trend for British indie labels and promoters to favour Welsh language groups (following John Peel’s own enthusiasm for them), and its fancy for any ethnic otherness, something that was born out of a post-colonial arbitrary pluralism that (still now) tastefully drapes difference with unthreatening veils of equivalence (‘tolerance’ above engagement). ‘Telephant’ had been a 1970s children’s TV show that BBC Wales used to make kids watch instead of Swap Shop or whatever Hanna Barbera fare was on before it. No matter how laudable and worthy the Welsh language cause might have been, for kids growing up in parts of Wales heavily anglicised by heavy industry (e.g. Bridgend) switching on the telly Saturday mornings met by low-budget and apparently patronising kids’ entertainment routines in a foreign language was a bit of a bummer. The same cultural priorities would get the band’s goat in the 80s and early 90s when they’d find it so hard to get really decent opportunities to put stuff on because they were neither Welsh language nor overtly Gallo-centric. A good example of how absurd this could be was an instance where a friend (and fan) of the band was unavailable for a certain engagement one autumn because the Arts Council in Wales were sending his Welsh-language glam rock band on an all-expenses tour to the Southern states of America. Later on, Gage and Bargefoot took to provocatively wearing union jack t-shirts when playing at Chapter after being sickened by a cultural-exchange exhibition that paired South Wales and Soweto on the basis that the oppression suffered by both communities was indistinguishable. Just to underline how Deeply rooted this tendency was, especially for readers outside the UK, Dylan Thomas was someone that was almost never mentioned through any official cultural channels in 1980s Wales, being a poet of the English language and a US émigré, generally an inconvenience.

The rest of the album comprises a handful of mildly interesting duo tracks, the last ever recordings to come out of Preswylfa (dubbed ‘Preswylfa Sounds’ by Hartford, who recorded his multi-tracked album Dr. Fekkesh’s Case Book there in the Summer of 1988), recorded by Bargefoot and Stews. They already sound a lot more like 1989 Sparrow, with a certain incompleteness to them that would soon be rectified by Gage.

Tracklisting:

- I Couldn’t Get It Up Tonite

- Dandruff

- Lyrict Apology

- Over

- Memories Of Roman Times

- Telephant

- Shell

- Big Black Hearse

- Neighbours In Transit

- Keep The Faith Brother

- My 3 Abortions 2

- Shirley

- Who Left The Gas On?

- Already Dead

Personnel:

Bill Bargefoot

Heaving Stews

Emma 100-Fingers

Tony Gage

plus Ceri Davies (drums) on 2, 3, 5, 9, 11 & 13

and Guy Williams (drums) on 6, 10 & 11

Recorded in the Hut, Preswylfa, and in concert at El Sico’s, Newport and Take Two, Sheffield

Radioactive Sparrow – 1730s (1988)

No one can remember now why it seemed appropriate to open this album with a song from the previous one. But there it is, that’s how the story goes. Tiffany had been a duo outing by Bargefoot and Stews, and somehow the logic seems to have been that ‘At Dinner,’ along with three other selections were honoured with a promotion to the next full-band release proper. Whatever the thinking, there’s no excuse for gratuitously filling album time with recycled material, and yet, on the other hand, the four songs’ place in the narrative continuity of 1730s feels appropriate.

Aside from the recycled cuts, the album comprises a quartet session from Preswylfa (the core trio being joined by Heaving Stews’s brother) and the band’s first ever, supremely controversial appearance at Clwb Ifor Bach (anglophonically known as ‘The Welsh Club’) on Cardiff’s Womanby Street, a locale that would become increasingly important in the band’s mythology during the early 90s, eventually having a later (1994) album named after it (for which stayed tuned… obviously). The band was invited to play by the legendary Mark ‘Sweaty T’ Taylor whose cultural sway over alt-fashion and nightlife in 1980s Cardiff was preeminent. Among other things he had started the Square Club (above the now-long-gone Radcliffe’s) and the Mars Bar on Churchill Way (or was it Charles Street?). In the spring of 1988, the city’s most self-consciously alt-trendy cognoscenti were patronising his Saturday night club Terra at Clwb Ifor Bach. He was, it seems, a distant admirer of Radioactive Sparrow (his long-term/lifelong girlfriend/partner, Jane Powell, had performed with Gwilly Edmondez in his one-off 1986 Bigger Geddy Numbers show at Chapter); the band regarded his invitation to play Terra as an unquestionable honour.

Heaving Stews’s mood on 1730s was acerbically belligerent, something that is evident on several levels. Among the Cardiff alt-scene’s contrived attire at this time were various kinds of faux-‘ethnic’ hats along with other garment accessories, which clearly raised his ire: the opening number from the gig, the album’s title-track-by-lyric (if you can say that), was a scornful tirade against any kind of tokenistic trend following: ‘What Decade Are You Into Now?’ proposes the ‘powdered wigs and stockinged feet’ of the 1730s as de rigueur for the ultimate fashion counter-statement. His vitriol throughout the show was unrelenting: ‘The Testicle Head’ weaves attacks on contemporary trends in TV (‘right to reply/video-vote’) into a series of lyrics aimed directly at a specific member of the audience (for whom the song’s title was conjured) who was making a particular nuisance of himself, berating the group for not meeting some assumed aesthetic imperative – Tim ‘Creepy’ Coulson (so the band were reliably informed) [pictured below] and his absent identical twin had reputedly completed a recent stint as studio assistants to Andy Warhol in New York (he can be heard telling Heaving to ‘give us something new,’ as he announces ‘The Testicle Head).

Throughout the show Stews was sporting a new dance that involved hopping on one leg (‘a new dance craze!’ being the main refrain in ‘The Testicle Head’). The final concert selection here, ‘ Hoppers,’ is his rallying call urging the crowd to join in – a genius move in an already very tense atmosphere, with several of Sweaty T’s most devoted super-hip taking their leave, resulting in one of the surprisingly rare instances of Sparrow being unplugged: Taylor was disgusted by the lumpen philistinism of his regulars, but felt nonetheless compelled to limit the damage to the night’s rep by fading in Kraftwerk’s ‘Musique Non-Stop’ (at the wrong speed) while fading out the band, thus drawing the concert to a premature end.

1730s is almost Brooce Boyes’s last album and almost Tony Gage’s first. The Preswylfa session was the last to feature the trio of Bargefoot/Boyes/Stews that had been the band’s core since 1985. Interestingly, Stews displays an impatience with the other two and their tendency to slip back into the extreme adolescent self-indulgence of the pretend-band of 1980-81; this is perfectly illustrated by the failed ‘(Minit) Ballad’ in which Bargefoot mischievously tries to persuade Jon (Brooce) to sing a ballad about his ‘first love,’ seeking to mine a favourite trope of rock music for laughs; Stews can be heard attempting to sabotage this indulgence, eventually banging the floor tom aggressively enough to make them stop, with Bargefoot sighing despairingly, ‘Ugh… Steve…’ as if he’s spoiling their fun. The result, however, of Stews’s vigilance to the group’s avant-pop potential is the timeless classic ‘Now Now Now,’ which ensues.

Such fun and games were staple, of course, but none of the band had any inkling that a year thence Boyes would be long gone, and so would this incarnation of Radioactive Sparrow. 1730s is the last Radioactive Sparrow album not to feature Tony Gage, although his voice can be heard on this album by virtue of his being in the audience at the Clwb Ifor show. Since his attendance at the November gig at Chapter, and expressing his admiration for the group’s approach, Bargefoot had furnished him with a bespoke compilation of Sparrow favourites. Whenever Stews or Bargefoot had bumped into him in town he had reminded them to tell him when Sparrow were playing again – which wasn’t that often at the time since Boyes and Stews lived in Plymouth. On the night of the Terra gig, with an hour to go before they took the stage, they suddenly realised they hadn’t told him, whereupon they jumped in the van and headed out to Roath, where they knew Gage lived, but didn’t have his address. By an absurd coincidence worthy of the most implausible film script, they happened upon him coming round a corner riding his (presciently cool drop-handle – except actually this was still the 80s, so I guess they were still actually current issue?) bicycle back from work. They hurriedly informed him of the imminent performance, and he said he’d be there. Which he was. He did. He was there, he did come to the gig. And was pleasantly shocked by a spirited antagonism with the crowd that had been wholly absent (since the evening had been utterly congenial) from the Chapter show.

Tracklisting:

- At Dinner

- What Decade Are You Into Now?

- Spoken English

- Your Bum Again

- The Testicle Head

- (Minit) Ballad

- Now Now Now

- The Re-Emergence Of The Tupperware Party

- Lemon Drop Danglin’

- Hoppers

- Promiser

- Second Coming

Personnel:

Heaving Stews

Bill Bargefoot

Brooce Boyes

plus Owen Powell (keybs) and Ceri Davies (drums) on tracks 2, 5 & 10

and David Hughes on 3, 6, 7 & 11

NB – tracks 1, 4, 8 & 12 also appear on Tiffany (album 37)