Radioactive Sparrow – Rockin’ On The Portoman (1989)

Rockin On The Portoman marks the onset of the portomam era, a period in which Radioactive Sparrow blew their game wide open, disavowing all the tenets they’d seemed to have observed about one-take, uncomposed pop made up in the very moment of historic inscription. Albums 44-49 constitute an extended requiem for the 1980s, a ghost-written suicide note for the greatest and most complicated decade in recorded popular music. Between the dawn of the 80s and its dismantling in tandem with the demise of Soviet state capitalism, Radioactive Sparrow had accounted for the awakening of adolescent sensibility to the torrid piss of Hades as hegemon while unilaterally resisting the tendency to relinquish unbridled play. Over the course of the next six albums, they dismembered pop music and crafted a vivid botch of its entrails that culminates in the sarcastic adieu of Spume‘s ‘Pube.’ Like the 15-a-week low-budget horror vids they were renting during this period, the music is gratuitously stank, revelled in cheaply close-up, neurotic detail.

The title (and era-demarcation it posed) denotes the group’s sudden and unexpected decision to start recording on a multitracker, namely the Tascam 244 cassette portastudio that Bargefoot had acquired in 1984 and which had been previously used to make demos with his rehearsing outfits (The Sculpture Drinks, Economy Of Islands) and solo experimental stuff (such as 1987’s Song Birds and 1988’s Nonchalance In Vain). The term ‘portoman’ came from Jason Davies relaying news from having bumped into Tony Gage in town some time late the previous year when the latter had borrowed said 244 to record some solo material (1988’s 4-Track Recordings); the way Davies reported it was by casually paraphrasing Gage saying ‘me and Rich[ard Bowers] have been rockin’ on the portoman…’

The reason for the leap into slightly more professional tech was due to the apparent deterioration (see the Angwitch triptych with its various channel cuts and buzzes) of the 1970s National Panasonic radio-cassette (from ca. 1975) whose stereo condenser mics had captured just about everything the band had ever done, using it like a camera, positioning sound sources in relation to the tape machine and performing to it. Over the years, the band developed an advance capacity for production that sidestepped the conventions of the established recording industry. Now, suddenly, they seized the new possibilities wildly and with one hand, the other remaining firmly gripped by the overriding anti-professionalist principles that had long defined their nous.

Throughout the portoman era, which was just over a year long (February 1989 to April 1990) the one principle that hey remained faithful to was the resistance to composing, rehearsing or re-recording music, true to one-shot capture, only now superimposed – not out of any high-minded reverence for some artistic principle but because getting bogged down by any hint of professionalism or industrial orthodoxy strained the joy out of the process. Everything you hear on these albums was made as quickly as it took to play each song twice – the group would improvise the first two tracks, then overdub tracks 3 and 4 at the same time, again without preparation or discussion except to decide who would play what. This went for all the albums made on the multitracker with the one exception of Spume which they spent about six weeks making, dropping in every few days to add a track here and there, even writing lyrics for some vocal parts.

Radioactive Sparrow is a mythology which, through the efforts of a handful of artists, has secretly inscribed itself into real history over the course of the last 32 years. As such, its history has been drastically scaled down from the usual chronology of traditional rock bands. While it is, ultimately, just a story, the fact that it really happened unbeknown to most people has created a situation for its members whereby the imagined and the understood are continually in a state of mutual flux. When Bill Bargefoot was around 6 or 7 years old, he discharged his four Action Man figurines from the anarchically internationalist army which had seen regular frontline service on the walls and in the flower beds of his garden, and had them form a band called Zunk. He got his sister to make them new clothes out of denim and paisley, and his Dad to hastily carve little wooden Strats – the fact that they were still in their army boots even had the advantage of being fashionably ahead of the game, this being the early 70s. Getting a bit carried away with the makeover, he tried shaving one of two bearded figures he possessed – using an unhoused razor blade he inadvertently gouged huge chunks out of the dude’s face, something he then tried to atone for by holding the flame of a match to the surface, which merely made the plastic melt and start bubbling, marking the tiny rocker with post-adolescent pocking. For the next couple of years, until ornithology took over, he would mock up little stage sets for Zunk to do special live appearances in. Tragically his folks were pathological anti-hoarders, and at some stage in the early 90s it seems Bargefoot’s mum sent the old WW2 ammo box in which Zunk was stored to the municipal dump at Stormy Down.

All of which serves to illustrate how, once Sparrow was up and ruining, all its developmental twists and turns similarly unfolded on the miniature scale of a young boy’s imaginative play. This went for both peaks and troughs. On a miniature scale, then, Rockin On The Portoman was an immensely important moment for the band – on the one hand it was their most successful and popular release to date, selling nearly 40 copies (!), while the impact of this sudden ‘success’ on Bargefoot’s life, in particular, was miniaturely momentous. …In October 1988, Bargefoot had registered for the Bachelor of Music degree at Goldsmiths College, London. Goldsmiths had this brilliant little media centre which was equipped with high-speed multiple cassette duplicators (that could run off four D46 copies in 3 minutes flat). In March of 1989, he brought back from a visit to Wales the master mix of the latest Sparrow album (… Portoman) and set about making 40 copies with covers tastefully done in red on yellow card. Having completed the process, he went to his composition class for which he didn’t know (probably because he’d been in Wales, recording) students had been asked to bring a recording of something they’d made or something that was a particularly big influence on them. How fortuitous, then, that Bargefoot happened to have 40 copies of his band’s new album on him! When it was his turn, the played the class ‘Harrat’n Hutt’n’ and ‘The Cattle Bridge.’ The reception among his fellow students was one of hilarity and rapturous approval, and some 10 copies were snapped up at 2 quid a go right there and then. The response from the class tutor, however, was to sourly ask the rhetorical question, ‘Didn’t we get over all that in the 60s?’ Bargefoot was deeply shocked by the level of cynicism on the part of the lecturer, Tim Ewers, along with its obvious disinclination to any sort of encouragement. At aged nearly 23, he wasn’t troubled so much on a personal level, but the fact that Ewers was inclined to display such an attitude to 18-19 year-old hopefuls was very depressing. It triggered the beginning of the end for Bargefoot at Goldsmiths, intent thereafter to openly goad not only Ewers but several other staff who peddled dishonest and irrelevant orthodoxy pap to their first years. Rather than anyone seeking to meet the challenge he posed, he was duly shown the door come June, something for which his piano tutor, John Tilbury, actually congratulated him – Tilbury, who, it seems, always had an uncomfortable relationship with his employers (they certainly undervalued him), had by then become a Sparrow fan and had passed several albums on to the legendary composer John White who himself became a long-term champion of the group (of which more in later episodes) and started playing them in his lectures at the London College of Music. This is what I’m talking about with Sparrow being a rock & roll history in miniature: for the likes of Peter Green and Syd Barrett, suddenly selling loads of records, becoming rich and famous, being misunderstood and getting undone by LSD, resulted in a career-wrecking crash; Radioactive Sparrow hit their big time selling 40 copies and Bargefoot got kicked out of college…

The music on this album tries to go everywhere. ‘Harrat’n Hutt’n’ bursts into life as the album’s opener, almost a manifesto in the extremes of what was suddenly available to the Kak imagination now that overdubbing was legitimised – it’s a wild celebration of ludic exaggeration set to a backdrop of incompetent free jazz. The lead vocal (and its lyrics, as such, though they’re hard to decipher) is based on a tape of Scottish traditional piping by William McLean, something that had come into Bargefoot’s possession utterly by accident. A week or so before the recording, Gabriel ‘Gabelli’ Sobin had stayed with Bargefoot at his halls of residence in Camberwell (the legendary Dover House on Cormont Road, hardly halls, really). They had indulged in a four-day extended derive, effectively, walking aimlessly around London, avoiding returning to the room they were staying in until 3 or 4 in the morning. As if to ceremoniously acknowledge the feat of their exhausting mileage they would sit on returning for 30 minutes or so listening to these bagpipes in quiet contemplation. The album unfolds from here through a broad range of styles and methods, the trio greedily raiding the pantry of ideas previously remote to their resolutely spartan phonography. ‘Sarah Jane Takes The Reigns,’ sung by Stews reading from page 3 of the Sun supplementing their topless babe with gratuitous punning themed for the Seoul Olympics (it was an old copy dredged up from God knows where), sets out to sound swankishly slick before capsizing the decorum of cool for its chaotic chorus slide riffs. What used to be side one closes with a composed (though unrehearsed) song about what was then a new news phenomenon, global warming – the crowning moment of ‘No More Winters’ is Gage’s echoing ‘the ozone layer’ in a booming Gloucester accent.

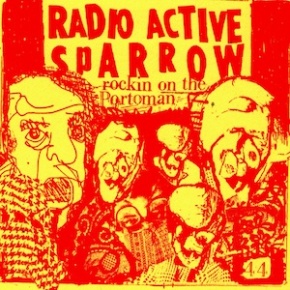

Even though Emma 100-Fingers was absent from the music, she provided the album with its superb cover art.

Tracklisting:

- Harrat’n Hutt’n

- Sarah Jane Takes The Reigns

- Music For Baby

- Empty Pockets

- No More Winters

- The Cattle Bridge

- Pond

- Bess Fren’s Girlfren

- Kim

- Please Tell Lisa

Personnel:

Tony Gage

Bill Bargefoot

Heaving Stews

Recorded in the Hut, early March 1989

Leave a comment